Social Insurance Programs

- Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI)

- Unemployment Insurance

- Workers' Compensation

- Temporary Disability Insurance

Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI)

The OASDI program—which for most Americans means Social Security—is the largest income-maintenance program in the United States. Based on social insurance principles, the program provides monthly benefits designed to replace, in part, the loss of income due to retirement, disability, or death. Coverage is nearly universal: About 96% of the jobs in the United States are covered. Workers finance the program through a payroll tax that is levied under the Federal Insurance and Self-Employment Contribution Acts (FICA and SECA). The revenues are deposited in two trust funds (the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund and the Federal Disability Insurance Trust Fund), which pay benefits and the operating expenses of the program. Benefit payments totaled over $343.2 billion in fiscal year 1996.

In 1996, 43.7 million persons received monthly benefits

In December 1996, 43.7 million persons were receiving monthly benefits totaling $29.4 billion. These beneficiaries included 30.3 million retired workers and their spouses and children, 7.4 million survivors of deceased workers, and 6.1 million disabled workers and their spouses and children.

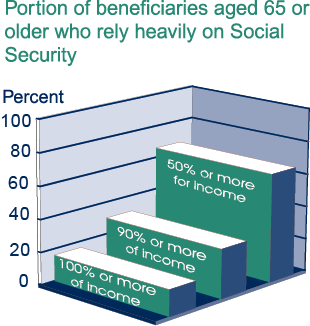

Social Security is an important source of retirement income for almost everyone; 3 in 5 beneficiaries aged 65 or older rely on it for at least half of their income. Social Security is also an important source of continuing income for young survivors of deceased workers: 98% of young children and their mothers or fathers are eligible for benefits should a working parent die. Four in five workers aged 21–64 and their families have protection in the event of a long-term disability.

Program Principles

Certain fundamental principles have shaped the development of the Social Security program. These basic principles are largely responsible for the program's widespread acceptance and support:

- Work Related—Economic security for workers and their families is based on their work history. Entitlement to benefits and the benefit level are related to earnings in covered work.

- No Means Test—Benefits are an earned right and are paid regardless of income from savings, pensions, private insurance, or other forms of nonwork income.

- Contributory—The concept of an earned right is reinforced by the fact that workers make contributions to help finance the benefits.

- Universal Compulsory Coverage—Workers at all income levels and their families have protection if earnings stop or are reduced due to retirement, disability, or death. With nearly all employment covered by Social Security, this protection continues when workers change jobs.

- Rights Clearly Defined in the Law—How much a person gets and under what conditions are clearly defined in the law and are generally related to facts that can be objectively determined. The area of administrative discretion is severely limited.

| Type of beneficiary | Number of beneficiaries December |

Average amount, December 1996 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 1960 | 1980 | 1996 | ||

| All beneficiaries | 222,488 | 14,844,589 | 35,618,840 | 43,736,836 | $672.80 |

| Retirement program | 148,490 | 10,599,021 | 23,243,078 | 30,310,865 | 703.58 |

| Retired workers | 112,331 | 8,061,469 | 19,582,625 | 26,898,072 | 744.96 |

| Wives and husbands | 29,749 | 2,269,384 | 3,018,008 | 2,970,226 | 383.50 |

| Children | 6,410 | 268,168 | 642,445 | 442,567 | 337.07 |

| Survivor program | 73,998 | 3,558,117 | 7,600,836 | 7,353,284 | 637.95 |

| Nondisabled widows and widowers | 4,437 | 1,543,843 | 4,287,930 | 5,027,901 | 706.85 |

| Disabled widows and widowers | . . . | . . . | 126,659 | 181,911 | 470.95 |

| Widowed mothers and fathers | 20,499 | 401,358 | 562,798 | 242,135 | 514.91 |

| Children | 48,238 | 1,576,802 | 2,608,653 | 1,897,667 | 487.17 |

| Parents | 824 | 36,114 | 14,796 | 3,670 | 613.54 |

| Disability program | . . . | 687,451 | 4,682,172 | 6,072,034 | 561.36 |

| Disabled workers | . . . | 455,371 | 2,861,253 | 4,385,623 | 703.94 |

| Wives and husbands | . . . | 76,599 | 462,204 | 223,854 | 171.39 |

| Children | . . . | 155,481 | 1,358,715 | 1,462,557 | 193.51 |

| Special age-72 beneficiaries | . . . | . . . | 92,754 | 653 | 197.27 |

Coverage

The Social Security Act of 1935 covered employees in nonagricultural industry and commerce only. Today, almost all jobs are covered.

Nearly all work performed by citizens and noncitizens is covered if it is performed within the United States (defined for Social Security purposes to include all 50 States, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, the territories of Guam and American Samoa, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Northern Mariana Islands).

In addition, the program covers work performed outside the United States by American citizens or resident aliens who are employed by an American employer, employed by a foreign affiliate of an American employer electing coverage for its employees, or (under certain circumstances) the self-employed.

Major Exclusions

- Federal civilian employees hired before 1/1/84

- Agricultural workers and domestic workers whose earnings do not meet certain minimum requirements

- Persons with very low net earnings from self-employment

The majority of workers excluded from coverage are in three major categories: (1) Federal civilian employees hired before January 1, 1984, (2) agricultural workers and domestic workers whose earnings do not meet certain minimum requirements, and (3) persons with very low net earnings from self-employment (generally less than $400 per year). The remaining few groups excluded from coverage are very small. An example is certain nonresident, nonimmigrant aliens temporarily admitted into the United States to study, teach, or conduct research. Certain family employment is also excluded (such as employment of children under age 18 by their parents).

Ministers and members of religious orders who have not taken a vow of poverty and Christian Science practitioners have their professional services covered automatically as self-employment unless within a limited period they elect not to be covered on the grounds of conscience or religious principle. Religious orders whose members have taken a vow of poverty may make an irrevocable election to cover their members as employees.

Employees of State and local governments are covered under voluntary agreements between the States and the Commissioner of Social Security. Each State decides whether it will negotiate an agreement and, subject to special conditions that apply to retirement system members, what groups of eligible employees will be covered. At present, more than 75% of State and local employees are covered.

Special rules of coverage apply to railroad workers and members of the uniformed services. Railroad workers have their own Federal insurance system that is closely coordinated with the Social Security program. If they have less than 10 years of railroad service, their railroad credits are transferred to the Social Security program. Under certain circumstances, members of the uniformed services may be given noncontributory wage credits in addition to the credits they receive for basic pay. The Social Security Trust Funds are reimbursed from Federal general revenues to finance noncontributory wage credits.

Eligibility for Benefits

In 1997, workers earn one Social Security credit for each $670 of annual earnings, up to four credits ($2,680 = 4 credits) per year

To qualify for Social Security a person must be insured for benefits. Most types of benefits require fully insured status, which is obtained by acquiring a certain number of credits (also called quarters of coverage) from earnings in covered employment. The number of credits needed depends on the worker's age and type of benefit.

Workers can acquire up to four credits per year, depending on their annual covered earnings. In 1997, one credit is acquired for each $670 in covered earnings. This earnings figure is updated annually, based on increases in average wages.

Retirement and Survivors Insurance

Persons are fully insured for benefits if they have at least as many credits (acquired at any time after 1936) as the number of full calendar years elapsing after age 21 and before age 62, disability, or death, whichever occurs first. For workers who attained age 21 before 1951, the requirement is one credit for each year after 1950 and before the year of attainment of age 62, disability, or death. Persons reaching age 62 after 1990 need 40 credits to qualify for retirement benefits.

For workers who die before acquiring fully insured status, certain survivor benefits are payable if they were currently insured—that is, they acquired 6 credits in the 13-quarter period ending with the quarter in which they died.

Annual Earnings Test.—Beneficiaries may have some or all benefits withheld, depending on the amount of their annual earnings. Benefits payable to a spouse and/or child may also be reduced or withheld due to the earnings of the retired worker. This provision, known as the earnings test (or retirement test) is in line with the purpose of the program—to replace some of the earnings from work that are lost because of the worker's retirement, disability, or death.

1997 Earnings Test

Age 70

No limit

Age 65–69

$1 less for every $3 over $13,500

Under age 65

$1 less for every $2 over $8,640

The dollar amount beneficiaries can earn without having their benefits reduced depends on their age. Persons aged 70 or older receive full benefits regardless of their earnings. In 1997, benefits for persons under age 65 are reduced $1 for each $2 of annual earnings in excess of $8,640; benefits for persons aged 65–69 are reduced $1 for each $3 of earnings above $13,500.

The exempt amounts for persons aged 65–69 will increase gradually to $30,000 in 2002, while amounts for those under age 65 will be indexed to the growth in average wages. After the year 2002, amounts for persons aged 65–69 will also be indexed to increases in average wages.

A “foreign work test” applies to beneficiaries who work outside the United States in noncovered employment. Benefits are withheld for any month in which more than 45 hours of work is performed. Generally, any benefits to family members are also withheld. The test is based on the amount of time the beneficiary is employed rather than on the amount of money the beneficiary earns because it is impractical to convert earnings in a foreign currency into specific dollar amounts.

Disability Insurance

To be eligible for disability benefits, workers must be fully insured and must meet a test of substantial recent covered work—that is, they must have credit for work in covered employment for at least 20 quarters of the 40 calendar quarters ending with the quarter the disability began. Young workers disabled before age 31 may qualify for benefits under a special insured status requirement. They must have credits in one-half the calendar quarters after age 21, up to the date of their disability, or, if disabled before age 24, one-half the quarters in the 3 years ending with the quarter of disability. Blind workers need only to be fully insured to qualify for benefits.

Disability = the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment that can be expected to result in death or that has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.

Disability Determination.—For purposes of entitlement, disability is defined as “the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment that can be expected to result in death or that has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.” A person's age, education, and work experience are considered along with the medical evidence in making a determination of disability. A less strict rule is provided for blind workers aged 55 or older. Such workers are considered disabled if, because of their blindness, they are unable to engage in SGA requiring skills and abilities comparable to those required in their past occupations.

The impairment must be of a degree of severity that renders the individual unable to engage in any kind of substantial gainful work that exists in the national economy, regardless of whether such work exists in the immediate area in which the individual lives, or if a specific job vacancy exists for that person, or if that person would be hired upon application for the work. The amount of earnings that ordinarily demonstrates SGA is set forth in regulations. For nonblind beneficiaries, earnings averaging more than $500 a month are presumed to represent SGA, and earnings below $300 generally indicate the absence of SGA. The SGA level for statutorily blind beneficiaries is $1,000 a month.

Unlike the Retirement and Survivors Insurance program, which is an entirely Federal program, the law mandates Federal-State cooperation in carrying out the DI program. Each State's Disability Determination Services (DDS) develops the medical evidence and makes an initial determination of disability, after SSA determines that the applicant is insured for benefits. DDS costs are reimbursed to the States by the Federal Government.

The applicant may appeal an unfavorable decision through a four-step process taken in the following order: a reconsideration of the initial decision; a hearing before an Administrative Law Judge; a review by the Appeals Council; and lastly, filing a civil suit in Federal District Court. A sample of DDS decisions is reviewed by SSA to assure consistency and conformity with national policies.

Applicants may be referred to the State vocational rehabilitation agency. If they are offered services and refuse them without good reason, benefits may be withheld. SSA pays for the cost of the rehabilitation services if such services result in a beneficiary's return to work at the SGA level for at least 9 continuous months.

Other Disabled Beneficiaries.—Monthly benefits at a permanently reduced rate are payable to disabled widow(er)s beginning at age 50, based on the same definition of disability that applies to workers. The disability must have occurred within 7 years after the spouse's death or within 7 years after the last month of previous entitlement to benefits based on the worker's earnings record.

Benefits are also payable to an adult child of a retired, disabled, or deceased worker if the child became disabled before age 22. The child must meet the same definition of disability that applies to workers.

Work Incentives

- Trial work period

- Extended period of eligibility

- Work excluded as not SGA

- Elimination of second waiting period for both cash and Medicare benefits

- Medicare buy-in

- Impairment-related expenses

Work Incentives.—Beneficiaries are allowed a trial work period to test their ability to work without affecting their eligibility for benefits. The trial work period can last up to 9 months (not necessarily consecutive) during which an individual's entitlement to benefits and benefit payment are unaffected by earnings, so long as the individual's impairment meets program standards. Months in which earnings are below a threshold amount, which is currently $200, do not count as months of trial work. At the end of the trial work period, a decision is made as to the individual's ability to engage in SGA. If the beneficiary is found to be working at SGA, disability benefits are paid for an additional 3 months (period of readjustment) and then cease; otherwise, benefits continue.

The law also includes other work incentive provisions: (1) A 36-month extended period of eligibility after a successful trial work period. This special benefit protection allows benefit payments during any month in the 36-month period in which earnings fall below $500. (2) The continuation of Medicare coverage for at least 39 months beyond the trial work period and, after that, the opportunity to purchase Medicare coverage when benefits terminate because of work. (3) Deductions from earnings for impairment-related work expenses in determining SGA. Deductible costs include such things as attendant care, medical devices, equipment, and prostheses.

Additionally, family benefits payable in disabled-worker cases are subject to a lower cap than the one that prevails for other types of benefits, because of concern that some disabled workers might be discouraged from returning to work because their benefits could exceed their predisability net earnings.

Type of Benefits

Monthly retirement benefits are payable at age 62 but are permanently reduced if claimed before the normal retirement age (currently, age 65). Benefits may also be payable to the spouse and children of retired-worker beneficiaries. A spouse receives benefits at age 62 or at any age if he/she is caring for a child under age 16 or disabled. A divorced spouse aged 62 or older who had been married to the worker for at least 10 years is also entitled to benefits. If the spouse has been divorced for at least 2 years, the worker who is eligible for benefits need not be receiving benefits for the former spouse to receive benefits. Benefits are payable to unmarried children under age 18, or aged 18–19 if they attend elementary or secondary school full time. A child can be the worker's natural child, adopted child, stepchild, and—under certain circumstances—a grandchild or stepgrandchild. A person aged 18 or older may also receive benefits under a disability that began before age 22.

Monthly benefits are payable to disabled workers after a waiting period of 5 full calendar months. This rule applies because Disability Insurance is not intended to cover short-term disabilities. Benefits terminate if the beneficiary medically improves and returns to work (at a substantial gainful activity level) despite the impairment. At age 65, beneficiaries are transferred to the retirement program. Benefits for family members of a disabled worker are payable under the same conditions as for those of retired workers.

Monthly benefits are payable to survivors of a deceased worker. A widow(er) married to the worker for at least 9 months (3 in the case of accidental death) may receive an unreduced benefit if claimed at age 65 (if the spouse never received a retirement benefit reduced for age). It is permanently reduced if claimed at age 60–64, and for disabled survivors at age 50–59. Benefits are payable to a widow(er) or surviving divorced spouse at any age who is caring for a child under age 16 or disabled. A surviving divorced spouse aged 60 or older is entitled to benefits if he or she had been married to the worker for at least 10 years. A deceased worker's dependent parent aged 62 or older may also be entitled to benefits.

Surviving children of deceased workers may receive benefits if they are under age 18, or are full-time elementary or secondary school students aged 18–19, or were disabled before age 22.

A lump sum of $255 is payable upon an insured worker's death, generally to the surviving spouse. If there is no surviving spouse or entitled child, no lump sum is payable.

| Type of benefit | Requirement for entitlement |

|---|---|

| Retired worker | Fully insured:

|

| Disabled worker | Fully insured and has 20 quarters of coverage in the 40 calendar quarters ending with the disability onset:

|

| Spouse or child (of a worker receiving retirement or disability benefits) | Spouse married to the worker for at least 1 year, or is the parent of the worker's child, and meets one of the following age requirements:

|

Divorced spouse, married to the worker for at least 10 years, and meets one of the following age requirements:

|

|

Child:

|

|

| Survivors (of a deceased worker) | Widow/widower:

|

Child:

|

|

Dependent parent aged 62 or older:

|

|

Lump-sum death payment:

|

|

| Note: Auxiliary and survivor benefits are subject to a family maximum amount. | |

| PIA = primary insurance amount. | |

Benefit Amounts

The OASDI benefit amount is based on covered earnings averaged over a period of time equal to the number of years the worker reasonably could have been expected to work in covered employment. Specifically, the number of years in the averaging period equals the number of full calendar years after 1950 (or, if later, after age 21) and up to the year in which the worker attains age 62, becomes disabled, or dies. In survivor claims, earnings in the year of the worker's death may be included. In general, 5 years are excluded. Fewer than 5 years are disregarded in the case of a worker disabled before age 47. The minimum length of the averaging period is 2 years.

For persons who were first eligible (attained age 62, became disabled, or died) after 1978, the actual earnings are indexed— updated to reflect increases in average wage levels in the economy. For persons first eligible before 1979, the actual amount of covered earnings is used in the computations. After a worker's average indexed monthly earnings (AIME) or average monthly earnings (AME) have been determined, a benefit formula is applied to determine the worker's primary insurance amount (PIA), on which all Social Security benefits related to the worker's earnings are based. The benefit formula is weighted to replace a higher portion of lower paid workers' earnings than of higher paid workers' earnings (although higher paid workers will always receive higher benefits).

For persons first eligible for benefits in 1997, the formula is:

90% of the first $455 of AIME, plus

32% of next $2,286 of AIME, plus

15% of AIME over $2,741.

The dollar amounts defining the AIME brackets are adjusted annually based on changes in average wage levels in the economy. As a result, initial benefit amounts will generally keep pace with future increases in wages. A special minimum PIA is payable to persons who have had covered employment or self-employment for many years at low earnings. It applies only if the resulting payment is higher than the benefit computed by the regular formula.

Persons who retire at age 65 (in 1997), with average earnings, have 45% of their prior year's earnings replaced by Social Security benefits. For those with maximum earnings the replacement rate is 25%; for minimum earners, 61%. The PIA is $1,326 for workers whose earnings were at or above the maximum amount that counted for contribution and benefit purposes each year and who retire at age 65 in 1997.

| Earnings level and beneficiary type | Pre-retirement earnings replaced (Workers retiring at age 65 in 1997) |

Disabled workers earnings replaced (Workers age 45 in 1997) |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum earnings ($62,700) | ||

| Worker | 25.4% | 27.7% |

| Worker/spouse | 38.1% | 41.5% |

| Average earnings ($24,706) | ||

| Worker | 45.3% | 44.8% |

| Worker/spouse | 67.9% | 67.2% |

| Low earnings ($11,118) | ||

| Worker | 61.0% | 60.4% |

| Worker/spouse | 91.4% | 85.0% |

After the initial benefit amount has been determined for the year of first eligibility, the amount is increased automatically each December (payable in the January checks) to reflect any increase in the Consumer Price Index. The 1997 cost-of-living adjustment is 2.9%. The benefit may be recomputed if, after retirement, the worker has additional earnings that produce a higher PIA.

The monthly benefit for a worker retiring at age 65 is equal to the PIA rounded to the next lower multiple of $1. For workers retiring before age 65, the benefit is actuarially reduced to take account of the longer period over which they will receive benefits. Currently, a worker who retires at age 62 receives 80% of the full benefit amount (20% reduction). The benefit is reduced 5/9 of 1% for each month of entitlement before age 65. The maximum reduction is 20% for those entitled to benefits for all 36 months between ages 62–65. A spouse who begins to receive benefits at age 62 receives 75% of the amount that would have been payable at age 65; a widow(er) at age 60 will be paid 71½% of the deceased spouse's PIA, as will a disabled widow(er) aged 50–59.

The normal retirement age (the age of eligibility for unreduced benefits) will be increased gradually from 65 to 67 beginning with workers who reach age 62 in the year 2000. The normal retirement age will be increased by 2 months per year in two stages—2000–2005 and 2017–2022—until it reaches age 67 for workers attaining age 62 in 2022 and later. During 2006–2016, the normal retirement age will remain at 66 for workers attaining age 62 in that period.

Benefits will continue to be payable at age 62 for retired workers and their spouses and at age 60 for widow(er)s, but the maximum benefit reduction for workers and spouses will be greater. Workers retiring before the normal retirement age will have benefits reduced by 5/9 of 1% for the first 36 months of receipt of benefits immediately preceding age 65, plus 5/12 of 1% for months in excess of 36 months (maximum reduction 30%).

| Full benefit at age | Retirees, spouses, and divorced spouses Date of birth* |

Widow(er)s and divorced widow(er)s Date of birth* |

|---|---|---|

| 65 | Prior to 1938 | Prior to 1940 |

| 65 and 2 months | 1938 | 1940 |

| 65 and 4 months | 1939 | 1941 |

| 65 and 6 months | 1940 | 1942 |

| 65 and 8 months | 1941 | 1943 |

| 65 and 10 months | 1942 | 1944 |

| 66 | 1943–1954 | 1945–1956 |

| 66 and 2 months | 1955 | 1957 |

| 66 and 4 months | 1956 | 1958 |

| 66 and 6 months | 1957 | 1959 |

| 66 and 8 months | 1958 | 1960 |

| 66 and 10 months | 1959 | 1961 |

| 67 | 1960 or later | 1962 or later |

| * Month and date are January 2 unless otherwise shown. | ||

Similarly, spouses of retired workers electing benefits before the normal retirement age in effect at the time will have their benefits reduced 25/36 of 1% for each of the first 36 months and 5/12 of 1% for up to 24 earlier months (maximum reduction 35%).

Workers who retire after age 65 have their benefits increased based on the delayed retirement credit. The credit is 5.0% of the PIA per year for workers attaining age 65 in 1996–97. It will increase gradually until it reaches 8% per year for workers attaining age 66 in 2009 or later.

Benefits for eligible family members are based on a percentage of the worker's PIA. A spouse or child may receive a benefit of up to 50% of the worker's PIA. A surviving widow's or widower's benefit is equal to as much as 100% of the amount of the deceased worker's PIA. The benefit of a surviving child is 75% of the worker's PIA.

The law sets a limit on the total monthly benefit amount to workers and their eligible family members. This limitation assures that the families are not considerably better off financially after the retirement, disability, or death of the worker than they were while the worker was employed.

Persons eligible for benefits based on their own earnings and as an eligible family member or survivor (generally as a wife or widow) will receive the full amount of the worker benefit, plus an amount equal to any excess of the other benefit over their own—in effect, the larger of the two.

Benefits for disabled workers are computed in much the same way as are benefits for retired workers. Benefits to the family members of disabled workers are paid on the same basis as those to the family of retired workers. The limitation on family benefits is, however, somewhat more stringent for disabled-worker families than for retired-worker or survivor families.

Taxation of Benefits

Up to 85% of Social Security benefits may be subject to Federal income tax depending on the taxpayer's amount of income (under a special definition) and filing status. The applicable definition of income is:

Adjusted gross income (before Social Security or Railroad Retirement benefits are considered), plus tax-exempt interest income—with further modification of adjusted gross income in some cases involving certain tax provisions of limited applicability among the beneficiary population—plus one-half of Social Security and Tier I Railroad Retirement benefits.

For married taxpayers filing jointly whose income under this definition is between $32,000 and $44,000, the amount of benefits included in gross income is the lesser of one-half of Social Security and Tier I Railroad Retirement benefits or one-half of income over $32,000. If their income exceeds $44,000, the amount of benefits included in gross income is the lesser of (1) 85% of Social Security and Tier I railroad retirement benefits or (2) the sum of $6,000 plus 85% of income over $44,000.

For married taxpayers filing separate returns, no exempt amounts are applicable. The amount of benefits included in the gross income is the lesser of 85% of Social Security or Tier I Railroad Retirement benefits, or 85% of income (as defined above). For individuals in all other filing categories, the amount of benefits to be included in gross income is determined in a manner analogous to that for married taxpayers filing jointly. The difference lies in the lower amounts of gross income exempted.

Financing

Tax Rate

Maximum taxable amount of earnings: $62,700

Tax rate for—

Employers and employees each: 6.20%

Self-employed persons: 12.40%

The OASDI program requires workers and their employers and self-employed persons to pay taxes on earnings in covered jobs up to the annual taxable maximum ($65,400 in 1997). This amount is automatically adjusted as wages rise. These taxes are deposited in two separate trust funds—the OASI Trust Fund and the DI Trust Fund.

The money received by the trust funds can be used only to pay the benefits and operating expenses of the program. Money not needed currently for these purposes is invested in interest-bearing securities guaranteed by the U.S. Government.

In addition to the Social Security taxes, trust fund income includes amounts transferred from the general fund of the U.S. Treasury, income from the taxation of benefits, and interest on invested assets of the funds. Transfers from the general fund include payments for gratuitous military service wage credits and for limited benefits to certain very old persons who qualify under special insured status requirements. Interest income on trust fund assets is derived from securities guaranteed by the U.S. Government.

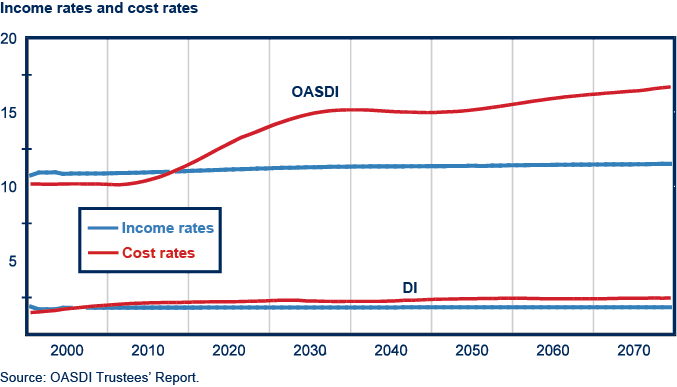

Based on 75-year actuarial forecasts, a schedule of current and future tax rates designed to produce sufficient revenues, together with other revenues, to finance the program over the long range is set forth in the law. This schedule also specifies what portion of total revenues collected is to be allocated to each of the Social Security programs.

The OASDI tax rate is 6.20% each for employees and employers. Self-employed persons pay at the combined employee-employer rate, or 12.40%. (Note: Medicare (HI) taxes are paid on total earnings. The tax rate, for both employee and employer is 1.45%.)

For self-employed persons, two deduction provisions reduce their OASDI and income tax liability. The intent of these provisions is to treat the self-employed in much the same manner as employees and employers are treated for purposes of Social Security and income taxes. The first provision allows persons to deduct from their net earnings from self-employment an amount equal to one-half their Social Security taxes. The effect of this deduction is intended to be analogous to the treatment of the OASDI tax paid by the employer, which is disregarded as remuneration to the employee for OASDI and income tax purposes. The second provision allows a Federal income tax deduction, equal to one-half of the amount of the self-employment taxes paid, which is designed to reflect the income tax deductibility of the employer's share of the OASDI tax.

A Board of Trustees is responsible for managing the OASDI Trust Funds and for reporting annually to Congress on the financial and actuarial status of the trust funds. This Board is comprised of six members—four of whom serve automatically by virtue of their positions in the Federal Government: The Secretary of the Treasury, who is the Managing Trustee, the Secretary of Labor, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and the Commissioner of Social Security. The other two members are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate to serve as public representatives.

Administration

Administrative expenses for OASDI were $3.0 billion in CY '96, or about 0.9% of benefit payments in the year

The Commissioner of Social Security is responsible for administering the OASDI program (except for the collection of FICA taxes, which is performed by the Internal Revenue Service of the Department of the Treasury), the preparation and mailing of benefit checks (or the payment of benefits through direct deposit), and the management and investment of the trust funds, which is supervised by the Secretary of the Treasury as Managing Trustee. The Commissioner is appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate for a 6-year term.

A bipartisan Advisory Board, which is composed of seven members who serve 6-year terms, examines issues regarding the Social Security system and advises the Commissioner on policies related to the OASDI (and SSI) programs.

The Social Security number (SSN) is the method used for posting and maintaining the earnings and employment records of persons covered under the Social Security program.

Employers withhold FICA taxes from their employees' paychecks and forward these amounts, along with an equal amount of employer tax, to the IRS on a regular schedule. By the end of February, employers file wage reports (Form W-2) with the Social Security Administration showing the wages paid to each employee during the preceding year. In turn, SSA shares this information with the IRS. Self-employed persons report their earnings for Social Security purposes and pay SECA taxes in connection with their Federal income tax return. Information from self-employment income reports is sent by IRS to SSA.

Reported earnings are posted to the worker's earnings record at SSA headquarters in Baltimore, Maryland. When a worker or his or her family member applies for Social Security benefits, the worker's earnings record is used to determine the claimant's eligibility for benefits and the amount of any cash benefits payable.

Payment is certified by SSA to the Department of the Treasury, which, in turn, mails out benefit checks or deposits the proper amounts directly into the beneficiary's bank account.

SSA's administrative offices and computer operations are located in its central office in Baltimore, Maryland. The Office of Disability and International Operations are also at that location. Program service centers in New York City, Philadelphia, Birmingham, Chicago, Kansas City (Missouri), and Richmond (California) certify benefit payments to the Department of the Treasury's Regional Disbursing Centers, maintain beneficiary records, review selected categories of claims, collect debts, and provide a wide range of other services to beneficiaries.

In addition, SSA has a nationwide network of about 1,300 field offices. The field operations are directed by Regional Commissioners and their staffs. Personnel in the field installations are the main points of public contact with SSA. They issue Social Security numbers, help claimants file applications for benefits, adjudicate Retirement and Survivors Insurance claims and help determine the amounts of benefits payable, and forward disability claims to a State DDS for a determination of disability. In calendar year 1995, administrative expenses of SSA amounted to $3.1 billion, or 0.9% of total benefits payable.

SSA also provides personal and automated services through its toll-free telephone number (1-800-772-1213). The 800-number network received about 62.3 million calls in calendar year 1995.

The Office of Hearings and Appeals administers the nationwide hearings and appeals program for SSA. The Appeals Council, located in Falls Church, Virginia, reviews hearing decisions.

Social Security and Foreign Systems

| Italy | 1979 |

|---|---|

| Germany | 1979 |

| Switzerland | 1980 |

| Belgium | 1984 |

| Norway | 1984 |

| Canada | 1984 |

| United Kingdom | 1985 |

| Sweden | 1987 |

| Spain | 1988 |

| France | 1988 |

| Portugal | 1989 |

| Netherlands | 1990 |

| Austria | 1991 |

| Finland | 1982 |

| Ireland | 1993 |

| Luxembourg | 1993 |

| Greece | 1994 |

Through international “totalization” agreements, the U.S. Social Security program is coordinated with the programs of other countries. These agreements benefit both workers and employers. First, they eliminate dual coverage and taxation when persons from one country work in another country and are required to pay social security taxes to both countries for the same work. Second, they prevent the loss of benefit protection for workers who have divided their careers between two or more countries.

The agreements allow SSA to totalize U.S. and foreign coverage credits only if the worker has at least six quarters of U.S. coverage. Similarly, a person may need a minimum amount of coverage under the foreign system in order to have U.S. coverage counted toward meeting the foreign benefit eligibility requirements. The United States currently has Social Security agreements in effect with 17 countries (Austria, Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom).

Benefits are generally payable to U.S. citizens regardless of where they reside. Benefits cannot be paid to an alien who is outside the United States for more than 6 months unless that person meets one of several exceptions in the law. For example, an exception is provided if (1) the worker on whose earnings the benefit is based had acquired at least 40 credits or had resided in the United States for at least 10 years, or (2) nonpayment of benefits would be contrary to a treaty obligation of the United States, or (3) the alien is a citizen of a country that has a social insurance or pension system of general applicability that provides for the payment of benefits to qualified U.S. citizens who are outside that country. Even if they qualify under these exceptions, aliens who are first eligible after 1984 for benefits as family members or survivors generally must also have resided in the United States for 5 years and been related to the worker during that time. Benefits are not payable to an alien living in a country in which the mailing of U.S. Government checks is prohibited.

| Country | Number of beneficiaries | Average benefit amount |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 314 | $182.07 |

| Belgium | 260 | $155.84 |

| Canada | 25,721 | $110.13 |

| Finland | 28 | $167.25 |

| France | 1,748 | $136.40 |

| Germany | 7,694 | $199.93 |

| Greece | 120 | $107.92 |

| Ireland | 264 | $138.92 |

| Italy | 5,098 | $119.26 |

| Netherlands | 653 | $120.52 |

| Norway | 1,750 | $136.92 |

| Portugal | 964 | $113.45 |

| Spain | 909 | $113.72 |

| Sweden | 523 | $135.58 |

| Switzerland | 1,509 | $132.77 |

| United Kingdom | 7,251 | $162.60 |

Unemployment Insurance

Unemployment insurance was initiated on a national basis in the United States as Title III and Title IX of the Social Security Act of 1935. It is a Federal-State coordinated program. Each State administers its own program within national guidelines promulgated under Federal law.

The program is designed to provide partial income replacement to regularly employed members of the labor force who become involuntarily unemployed. To be eligible for benefits a worker must register at a public employment office, must have a prescribed amount of employment and earnings during a specified base period, and be available for work and able to work. In most States, the base period is the first four quarters of the last five completed calendar quarters preceding the claim for unemployment benefits.

The amount of the weekly benefit amount a worker may receive while unemployed varies according to the benefit formula used by each State and the amount of the worker's past earnings. All States establish a ceiling on the maximum amount a worker may receive.

The number of weeks for which unemployment benefits can be paid ranges from 1 to 39 weeks. The most common duration is 26 weeks for the regular permanent program. Workers who have exhausted their unemployment benefits in the regular program may be eligible for additional payments for up to 13 weeks under a permanent program for extended benefits during periods of very high unemployment. Federal unemployment benefits have been established for several groups, including Federal military and civilian personnel.

The Department of Labor is responsible for ascertaining that the State unemployment insurance programs conform with Federal requirements. Unemployment benefits and funding for administration of the program generally are financed from taxes paid by employers on workers' earnings up to a set maximum.

Background

In 1932, the State of Wisconsin established the first unemployment insurance law in the United States, which served as a forerunner for the unemployment insurance provisions of the Social Security Act of 1935. The existence of the Wisconsin law, concerns over the constitutionality of an exclusively Federal system, and uncertainties about untried aspects of administration were among the factors that led to the Federal-State character of the system (unlike the old-age insurance benefit provisions of the Social Security legislation, which are administered by the Federal Government alone).

The Social Security Act provided two inducements to the States to enact unemployment insurance laws. A uniform national tax was imposed on the payrolls of industrial and commercial employers who employed 8 or more workers in 20 or more weeks in a calendar year. Employers who paid a tax to a State with an approved unemployment insurance law could credit up to 90% of their State tax against the national tax. Thus, employers in States without an unemployment insurance law would have little advantage in competing with similar businesses in States with such a law, because they would still be subject to the Federal payroll tax. Moreover, their employees would not be eligible for benefits. As a further inducement, the Social Security Act authorized grants to States to meet the costs of administering their systems.

By July 1937, all 48 States, the then territories of Alaska and Hawaii, and the District of Columbia had passed unemployment insurance laws. Puerto Rico later established its own unemployment insurance program, which was incorporated into the Federal-State system in 1961. Similarly, a program for workers in the Virgin Islands was added in 1978.

Federal law requires State unemployment insurance programs to meet certain requirements if employers are to receive their offset against the Federal tax and if the State is to receive Federal grants for administration. These requirements are intended to assure that State systems are fairly administered and financially secure.

One of these requirements is that all contributions collected under State laws be deposited in the unemployment trust fund in the Department of the Treasury. The fund is invested as a whole, but each State has a separate account to which its deposits and its share of interest on investments are credited. A State may withdraw money from its account at any time, but only to pay benefits.

Thus, unlike the workers' compensation and temporary disability insurance benefits in the majority of States, unemployment insurance benefits are paid exclusively through a public fund. Private plans cannot be substituted for the State plan.

Aside from Federal standards, each State has major discretion regarding the content and development of its unemployment insurance law. The State itself decides the amount and duration of benefits (except for certain Federal requirements concerning Federal-State Extended Benefits); the contribution rates (within limits); and, in general, eligibility requirements and disqualification provisions. The States also directly administer their programs— collecting contributions, maintaining wage records (where applicable), taking claims, determining eligibility, and paying benefits to unemployed workers.

Coverage

At the end of 1995, approximately 113 million workers were in jobs covered by unemployment insurance. Originally, coverage was limited to employment covered by the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA), primarily industrial and commercial workers in private industry. However, several Federal laws (such as the Employment Security Amendments of 1970 and the Unemployment Compensation Amendments of 1976) substantially increased both the number and types of workers protected under the State programs.

Private employers in industry and commerce are subject to the law if they employ one or more individuals on 1 day in each of 20 weeks during the current or preceding year, or if they paid total wages of $1,500 or more during any calendar quarter in the current or preceding year.

Agricultural workers are covered on farms with a quarterly payroll of at least $20,000 or employing 10 or more persons in 20 weeks of the year. A domestic employee in a private household is subject to FUTA if its employer paid wages of $1,000 or more in a calendar quarter. Self-employed individuals and workers employed by their own families are excluded from coverage.

Before 1976, State and local government and most nonprofit organizations were exempt from FUTA. However, most employment in these groups now must be covered by State law as a condition for securing Federal approval. Local governments and nonprofit employers have the option of making contributions as under FUTA, or of reimbursing the State for benefit expenditures actually made.

Elected officials, legislators, members of the judiciary, and the State National Guard are still excluded, as are employees of nonprofit organizations that employ fewer than four workers in 20 weeks in the current or preceding calendar year. However, many States have extended coverage beyond the minimum required by Federal legislation.

Federal civilian employees and ex-servicemembers have been brought under the unemployment insurance system through special Federal legislation. Their benefits are financed through Federal funds, but administered by the States and paid in accordance with State laws. Railroad workers are covered by a separate unemployment insurance law enacted by Congress. (This law is described in the section on programs for railroad workers.)

Eligibility for Benefits

Unemployment benefits are available as a matter of right (that is, without a means test) to unemployed workers who have demonstrated their attachment to the labor force by a specified amount of recent work and/or earnings in covered employment. All workers whose employers contribute to or make payments in lieu of contributions to State unemployment funds are eligible if they become involuntarily unemployed and are able to work, available for work, and actively seeking work.

Workers must also meet the eligibility and qualifying requirements of the State law. Workers who meet these eligibility conditions may still be denied benefits if they are found to be responsible for their own unemployment.

The benefit may be reduced if the worker is receiving certain types of income—pension, back pay, or workers' compensation for temporary partial disability. Unemployment benefits are subject to Federal income taxes.

Work Requirements

A worker's monetary benefit rights are based on his or her employment in covered work over a prior reference period, called the “base period,” and these benefit rights remain fixed for a “benefit year.” In most States, the base period is the first four quarters of the last five completed calendar quarters preceding the claim for benefits.

Six States specify a flat minimum amount of base period earnings, ranging from $1,000 to $2,964, to qualify. One-fourth of the States express their earnings requirements in terms of a multiple of the benefit for which the individual will qualify (such as 30 times the weekly benefit amount). Most of these jurisdictions, however, have an additional requirement that wages be earned in more than one calendar quarter or that a specified amount of wages be earned in the calendar quarter other than that in which the claimant had the most wages.

Almost half the States simply require base period wages totaling a specified multiple—commonly 1½ of the claimant's high-quarter wages. Seven States require a minimum number of weeks of covered employment (minimum number of hours in one State), generally reinforced by a requirement of an average or minimum amount of wages per week.

If the unemployed worker meets the State requirements, his or her eligibility extends throughout a “benefit year,” a 52-week period usually beginning on the day or the week for which the worker first filed a claim for benefits. No State permits a claimant who received benefits in one benefit year to qualify for benefits in a second benefit year unless he or she had intervening employment.

Other Requirements

All States require that for claimants to receive benefits, they must be able to work and must be available for work—that is, they must be in the labor force and their unemployment must be due to lack of work. One evidence of ability to work is the filing of claims and registration for work at a State public employment office. Most State agencies also require that the unemployed worker make an independent job-seeking effort.

Eleven States have added a proviso that no individual who has filed a claim and has registered for work shall be considered ineligible during an uninterrupted period of unemployment because of illness or disability, so long as no work, which is considered suitable but for the illness or disability, is offered and refused after becoming ill or disabled. In Massachusetts the period during which benefits will be paid is limited to 3 weeks and in Alaska 6 consecutive weeks.

Most States have special disqualification provisions that specifically restrict the benefit rights of students who are considered not available for work while attending school. Federal law also restricts benefit eligibility of some groups of workers under specified conditions: school personnel between academic years, professional athletes between sports seasons, and aliens not present in the United States under color of law.

The major reasons for disqualification for benefits are voluntary separation from work without good cause; discharge for misconduct connected with the work; refusal, without good cause, to apply for or accept suitable work; and unemployment due to a labor dispute. In all jurisdictions, disqualification serves at least to delay receipt of benefits. The disqualification may be for a specific uniform period, for a variable period, or for the entire period of unemployment following the disqualifying act. Some States not only postpone the payment of benefits but also reduce the amount due to the claimant. However, benefit rights cannot be eliminated completely for the whole benefit year because of a disqualifying act other than discharge for misconduct, fraud, or because of disqualifying income (that is, workers' compensation, holiday pay, vacation pay, back pay, and dismissal payments). Also, no State may deny unemployment insurance benefits when a claimant undergoes training in an approved program.

The Federal Unemployment Tax Act also provides that no State can deny benefits if a claimant refuses to accept a new job under substandard labor conditions, or where required to join a company union or to resign from or refrain from joining any bona fide labor organization. However, in all States unemployment due to labor disputes results in postponing benefits, generally for an indefinite period depending on how long the unemployment lasts because of the dispute. State laws vary as to how this disqualification applies to workers not directly involved.

Under Federal law, States are required under certain conditions to reduce the weekly benefit by the amount of any governmental or other retirement or disability pension, including Social Security benefits and Railroad Retirement annuities. States may reduce benefits on a less than dollar-for-dollar basis to take into account prior contributions by the worker to the pension plan.

In nearly half the States, workers' compensation either disqualifies the worker for unemployment insurance for the week concerned, or reduces the unemployment insurance benefit by the amount of the workers' compensation. Wages in lieu of notice or dismissal payments also disqualify a worker for benefits or reduce his or her weekly benefit in half the States.

Types and Amounts of Benefits

During 1995, the average weekly number of persons paid unemployment benefits under the regular programs (including State programs and programs for Federal employees and ex-servicemembers) was 2.6 million. Benefit payments totaled $21.9 billion, of which $21.3 billion was expended under State programs and $640 million to Federal employees and ex-servicemembers. The average weekly benefit was $187 and the average duration was 14.7 weeks.

Under all State laws, the amount payable for a week of total unemployment varies with the worker's past wages within minimum and maximum limits. In most of the States, the formula is designed to compensate for a fraction of the usual weekly wage (normally about 50%), subject to specified dollar maximums. The benefits provisions under State unemployment insurance laws are shown in Appendix III.

Three-fourths of the laws specify a formula that computes weekly benefits as a fraction of wages in one or more quarters of the base period—most commonly, the quarter during which wages were highest, because this quarter most nearly reflects full-time work. In most of these States, the same fraction is used at all benefit levels. The other laws provide for a weighted schedule that gives a greater proportion of high-quarter wages to lower-paid workers. Six States compute the weekly benefit amount as a percentage of annual wages, and five States base it directly on average weekly wages during a specified recent period.

Each State establishes a maximum weekly benefit, either a fixed dollar amount or a flexible ceiling. Under the latter arrangement, adopted in 35 jurisdictions, the maximum is adjusted automatically in accordance with the weekly wages of covered employees and is expressed as a percentage of the Statewide average—varying from 49.5% to 70%. Such provisions remove the need for amending the maximum as wage levels change.

The maximum weekly benefit for all States varies from $133 to $362 (excluding allowances for dependents provided by 13 jurisdictions). Because statutory increases in the maximum tend to lag behind increases in wage levels, the maximum in States with fixed amounts often reduces the benefit amounts of workers to below the 50% level. Minimum benefits—ranging from $5 to $87 a week—are provided in every State.

All States pay the full weekly benefit amount when a claimant has had some work during the week, but has earned less than a specified (relatively small) sum. In the majority of States, this amount is defined as a wage that is earned in a week of less than full-time work and that is less than the claimant's regular weekly benefit amount. All States also provide for the payment of reduced weekly benefits—partial payments—when earnings exceed that specified amount.

Twelve States and the District of Columbia provide additional allowances for certain dependents. They all include children under specified ages (16, 18, or 19 and, generally, older if incapacitated); nine States provide for a nonworking spouse; and three States cover other dependent relatives. The amount paid per dependent varies considerably by State but generally is $20 or less per week and, in the majority of States, it is the same for each dependent.

All but 11 States require a waiting period of one week of total unemployment before benefits can begin. Three States pay waiting-period benefits retroactively if unemployment reaches a certain duration or if the employee returns to work within a specified time.

All but two jurisdictions set a statutory maximum of 26 weeks of benefits in a benefit year. However, only nine jurisdictions provide the same maximum for all claimants. The remaining 44 jurisdictions vary the duration of benefits through formulas that relate potential duration to the amount of former earnings or employment—generally by limiting total benefits to a certain fraction of base period earnings or to a specified multiple of the weekly benefit amount, whichever is less.

| State | Regular 1 | Average weekly benefit | Average compensable duration (in weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | $4,736,798 | $183.02 | 14.92 |

| Alabama | 51,002 | 141.40 | 10.41 |

| Alaska | 18,919 | 168.87 | 15.01 |

| Arizona | 46,806 | 147.60 | 14.31 |

| Arkansas | 38,969 | 169.32 | 12.14 |

| California | 652,690 | 152.81 | 16.97 |

| Colorado | 41,488 | 206.67 | 12.45 |

| Connecticut | 98,849 | 213.81 | 16.60 |

| Delaware | 23,866 | 230.06 | 15.58 |

| District of Columbia | 25,151 | 233.58 | 19.08 |

| Florida | 191,370 | 175.09 | 14.27 |

| Georgia | 71,448 | 164.69 | 9.59 |

| Hawaii | 47,624 | 206.58 | 16.47 |

| Idaho | 14,790 | 176.13 | 12.19 |

| Illinois | 260,999 | 204.26 | 17.20 |

| Indiana | 49,066 | 177.48 | 11.19 |

| Iowa | 32,819 | 196.45 | 12.08 |

| Kansas | 32,114 | 201.66 | 13.42 |

| Kentucky | 46,651 | 170.49 | 12.31 |

| Louisiana | 35,163 | 127.85 | 14.32 |

| Maine | 19,044 | 170.20 | 14.07 |

| Maryland | 78,946 | 193.00 | 15.77 |

| Massachusetts | 167,770 | 246.13 | 16.35 |

| Michigan | 192,969 | 133.54 | 11.45 |

| Minnesota | 59,372 | 218.51 | 14.64 |

| Mississippi | 32,312 | 140.61 | 13.64 |

| Missouri | 63,007 | 150.54 | 13.35 |

| Montana | 9,605 | 159.52 | 14.20 |

| Nebraska | 10,373 | 156.34 | 11.54 |

| Nevada | 31,910 | 192.91 | 13.85 |

| New Hampshire | 8,611 | 158.81 | 9.61 |

| New Jersey | 309,518 | 247.86 | 17.31 |

| New Mexico | 18,018 | 160.53 | 16.20 |

| New York | 445,592 | 203.73 | 19.65 |

| North Carolina | 89,526 | 194.13 | 9.22 |

| North Dakota | 4,519 | 167.21 | 12.57 |

| Ohio | 137,334 | 197.23 | 13.66 |

| Oklahoma | 24,620 | 173.92 | 12.78 |

| Oregon | 84,489 | 191.02 | 15.45 |

| Pennsylvania | 340,281 | 205.43 | 16.81 |

| Puerto Rico | 55,940 | 93.87 | 18.61 |

| Rhode Island | 40,421 | 220.59 | 15.61 |

| South Carolina | 48,328 | 166.19 | 10.94 |

| South Dakota | 2,563 | 144.42 | 10.94 |

| Tennessee | 72,653 | 155.34 | 11.88 |

| Texas | 247,676 | 187.77 | 15.69 |

| Utah | 13,892 | 196.22 | 10.74 |

| Vermont | 9,664 | 162.38 | 14.50 |

| Virginia | 41,346 | 173.29 | 10.22 |

| Virgin Islands | 1,237 | 160.74 | 15.62 |

| Washington | 174,178 | 211.67 | 18.57 |

| West Virginia | 28,395 | 174.70 | 14.86 |

| Wisconsin | 87,869 | 192.59 | 12.10 |

| Wyoming | 5,038 | 180.69 | 14.39 |

| 1 Includes extended benefits of $527 million in Alaska and $8,817 million in Puerto Rico. | |||

| Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Service, Division of Actuarial Services, UI Data Summary, December 1996. | |||

Extended Benefits

In the 1970's, a permanent Federal-State program of extended benefits was established for workers who exhaust their entitlement to regular State benefits during periods of high unemployment. The program is financed equally from Federal and State funds. Extended Benefits are triggered when unemployment among insured workers in an individual State averages 5% or more over a 13-week period, and is at least 20% higher than the rate for the same period in the 2 preceding years. If the insured unemployment rate reaches 6% a State may, at its discretion, disregard the 20% requirement.

Once triggered, extended benefit provisions remain in effect for at least 13 weeks. When a State's benefit period ends, extended benefits to individual workers also end, even if they have received less than their potential entitlement and are still unemployed. Further, once a State's benefit period ends, another Statewide period cannot begin for at least 13 weeks.

Most eligibility conditions for extended benefits are determined by State law (and they are payable at the same rate as the regular State weekly amount). However, under Federal law a claimant applying for extended benefits must have had 20 weeks in full-time employment (or the equivalent in insured wages) and must meet special work requirements. A worker who has exhausted regular benefits is eligible for a 50% increase in duration, to a maximum of 13 weeks of extended benefits. There is, however, an overall maximum of 39 weeks of regular and extended benefits. Because of the way extended benefits were triggered, only nine jurisdictions qualified for them during the economic downturn of 1991.

The Unemployment Compensation Amendments of 1992 (P.L. 102-318), modified the permanent Extended Benefits program to provide more effective protection on an ongoing basis. Effective March 7, 1993, States had the option of amending their laws to use alternative total unemployment rate triggers, in addition to the current insured unemployment rate triggers. Under this option, extended benefits would be paid when the State's seasonally adjusted total unemployment rate for the most recent 3 months is at least 6.5%, and that rate is at least 110% of the State average total unemployment rate in the corresponding 3-month period in either of the 2 preceding years.

States triggering the extended benefits program using other triggers would provide the regular 26 weeks of unemployment benefits, in addition to 13 weeks of extended benefits (the same number provided previously). States that have opted for the total unemployment rate trigger will also amend their State laws to add an additional 7 weeks of extended benefits (for a total of 20 weeks) when the total unemployment rate is at least 8% and is 110% of the State's total unemployment rate for the same 3 months in either of the 2 preceding years.

Financing

The Unemployment Trust Fund in the Federal unified budget contains a separate account for each of the States, the District of Columbia, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico. These 53 jurisdictions deposit their respective unemployment taxes in their accounts and withdraw funds to cover the costs of regular State benefits and half of the extended benefits program. Three additional Federal accounts are for administration, extended benefits, and loans to States; they are funded by the Federal unemployment tax.

Effective January 1985, all employers covered by the Federal Unemployment Tax Act are charged 6.2% of the first $7,000 annually for each worker's covered wages. However, employers do not actually pay the full amount because they credit toward their Federal tax the payroll tax contributions that they paid into a State unemployment insurance program. Their credit may also include any savings on the State tax achieved under an approved experience rating plan, as described below.

The credit available to employers in a State may be reduced if the State has fallen behind on repayment of loans to the Federal Government. Many States have taken out such loans when their reserves were depleted during periods of high unemployment. These loans to States had been interest free, but beginning April 1982, interest has been payable except on certain short-term “cash flow” loans. As of January 1, 1996, no State had a loan outstanding.

Effective January 1985, the total credit may not exceed 5.4% of taxable wages. The remaining 0.8%, including a 0.2% temporary surcharge, is collected by the Federal Government. The permanent 0.6% portion is used for the expenses of administering the unemployment insurance program for the 50% share of the costs of extended benefits, and for loans to States. Any excess is distributed among the States in proportion to their taxable payrolls. The “temporary” 0.2% FUTA surcharge was added in 1977 and was extended through 1998 by a number of public laws.

All States finance unemployment benefits through employer contributions. There is no Federal tax on employees, and only three States collect employee contributions. In January 1996, 41 jurisdictions had set their tax bases higher than the $7,000 Federal base.

Most States have a standard tax rate of 5.4% of taxable payroll. However, the actual tax paid depends on the employer's record of employment stability, measured generally by benefit costs attributable to former employees. All jurisdictions use this system, called experience rating. Employers with favorable benefit cost experience are assigned lower rates than those with less favorable experience. Experience rating systems vary widely among the States. In 50 jurisdictions, the amount of benefits paid to former workers is the basic factor in measuring an employer's experience. The other jurisdictions rely on the number of separations from an employer's service, or the amount of decline in covered payrolls.

Contribution rates may also be modified according to the current balance of each State's Unemployment Trust Fund. When the balance falls below a specified level, rates are raised. In some States, it is possible for an employer with a good experience rating to be assigned a tax rate as low as 0%; the maximum in three States is 10%.

Benefits are commonly charged against all employers who paid the claimant wages during the base period, either proportionately or in inverse order of employment. However, a few States charge benefits exclusively to the separating employer. In some, benefits paid after a disqualification are not charged to any employer's account.

In 1995, the estimated national average employer contribution rate actually paid was 2.3% of taxable payroll, or 0.8% of total wages in covered work. The average contribution rate varied widely by State, however. The percent of State taxable payroll ranged from 0.6 to 4.9; the percent of total wages from 0.2 to 2.1.

Disaster Unemployment Assistance (DUA) is paid out of funds provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Benefits for former Federal civilian employees, including postal workers (and, after October 1, 1983, former members of the Armed Forces) are paid out of the Federal Employees Compensation Account (FECA) in the Unemployment Trust Fund, subject to reimbursement by the former employing agency.

Administration

States have the direct responsibility for establishing and operating their own unemployment insurance programs, while Federal unemployment insurance tax collections are used to finance expenses deemed necessary for proper and efficient administration. State unemployment insurance tax collections are used solely for the payment of benefits, and may not be used for any program administration cost, nor for training, job search, or job relocation payments. However, several States collect a supplementary tax for the administration of their unemployment insurance laws because funds appropriated each year by Congress out of the proceeds of the earmarked Federal unemployment tax for “proper and efficient administration” have not proven adequate.

Federal regulations do not specify the form of the organization administering unemployment insurance or its place in the State government. Twenty-eight States have placed their employment security agencies in the Department of Labor or under some other State agency, while the others rely on independent departments, boards, or commissions. Advisory councils have been established in all but four jurisdictions; 46 of them are mandated by law. These councils assist in formulating policy and addressing any problems related to the administration of the Employment Security Act. In most States, they include equal representation of labor and management, as well as representatives of the public interest.

State agencies operate through local full-time unemployment insurance and employment offices that process claims for unemployment insurance and also provide a range of job development and placement services. State employment offices were established by Congress in 1933 under the Wagner-Peyser Act, and thus actually antedate the unemployment insurance provisions of the Social Security Act. Federal law provides that the personnel administering the program must be appointed on a merit basis, with the exception of those in policymaking positions.

Federal law also requires that States must provide workers whose claims are denied an opportunity for a fair hearing before an impartial tribunal. Generally, there are two levels of administrative appeal: first to a referee or tribunal, and then to a board of review. Decisions of the board of review may be appealed to the State courts in all jurisdictions.

Generally, claims must be filed within 7 days after the week for which the claim is made, unless there is good cause for late filing. They must continue to be filed throughout the period of unemployment, usually biweekly and by mail. Benefits are paid on a biweekly basis in most States.

All the States have adopted interstate agreements for the payment of benefits to workers who move across State lines. They also have made special wage-combining agreements for workers who earned wages in two or more States.

The Federal functions of the unemployment insurance program are chiefly the responsibility of the Employment and Training Administration's Unemployment Insurance Service in the U.S. Department of Labor. It verifies each year that State programs conform with Federal requirements, provides technical assistance to the State agencies, and serves as a clearinghouse for statistical data. The Internal Revenue Service in the Department of the Treasury collects FUTA taxes, and the Treasury also maintains the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund.

Workers' Compensation

Workers' compensation was the first social insurance to develop widely in the United States. In 1908, the first workers' compensation program covering certain Federal civilian employees in hazardous work was enacted. Similar laws were passed in 1911 in some States for workers in private industry, but not until 1949 had all States established programs to furnish income-maintenance protection to workers disabled by work-related illness or injury. For the next several decades, State laws expanded coverage, raised benefits, and liberalized eligibility requirements and increased the scope of protection in other ways.

Today, such laws are in effect in all the States, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. In addition, three separate programs cover longshore, harbor, and other maritime workers; Federal employees; and coal miners.

Workers' compensation laws very widely among the States with regard to the number of weeks for which benefits may be paid and the amount of benefits payable. Payments for total disability are generally based on the worker's wages at the time of injury— usually 66⅔% of weekly wages, up to a statutory maximum.

Workers' compensation programs are almost exclusively financed by employers on the principle that the cost of work accidents is part of production expenses. Costs are influenced by the hazards of the industry and the method used to insure for liability. A few State laws contain provisions for nominal employee contributions for hospital and medical benefits.

Coverage

State and Federal workers' compensation laws cover the Nation's wage and salary labor force. Common coverage exemptions are domestic service, agricultural employment, and casual labor, although some prog rams cover agricultural and domestic workers. Many programs exempt employees of nonprofit, charitable, or religious institutions; some limit coverage to workers in hazardous occupations.

The coverage of State and local public employees differs widely among State programs. States may provide full coverage, specifying no exclusions. Some have broad coverage, excluding only such groups as elected or appointed officials. Other programs limit coverage to public employees of specified political subdivisions or to employees engaged in hazardous occupations. In some States, coverage of government employees is optional with the State, city, or other political subdivision.

Two other major groups outside the coverage of workers' compensation laws are railroad employees engaged in interstate commerce and seamen in the merchant mar ine. These workers are covered by Federal statutory provisions for employer liability that give the employee the right to charge an employer with negligence. The employer is barred from pleading the common law defenses of assumed r isk of the employment, negligence of fellow workers, and contr ibutory negligence.

The programs are compulsory for most covered jobs in private industry except in New Jersey, South Carolina, and Texas. In these States, the programs are elective—that is, employers may accept or reject co verage under the law; but if they reject such coverage, they lose the customary common law defenses against suits by employees.

The programs use varying methods to assure that compensation will be paid when it is due. No program relies on general taxing power to finance workers' compensation. Employers in most programs may carry insurance against work accidents or give proof of financial ability to carry their own risks. Federal employees are protected through a federally financed and operated system.

Eligibility for Benefits

Although at first virtually limited to injuries or diseases traceable to industrial “accidents,” the scope of the programs has broadened to cover occupational diseases as well. However, protection against occupational disease is still restricted because of time limitations, prevalent in many States, on the filing of claims. That is, benefits for diseases with long latency periods are not payable in many cases because most State laws pay benefits only if the disability or death occurs within a relatively short period after the last exposure to the occupational disease (such as 1–3 years) or if the claim is filed within a similar time after manifestation of the disease or after disability begins. Some programs restrict the scope of benefits in cases of dust-related diseases such as silicosis and asbestosis.

These eligibility restrictions reflect the problems associated with determining the cause of disease . Work-related ailments such as heart disease, respiratory disorders, and other common ailments may be brought on by a variety of traumatic agents in the individual's environment. The role of the workplace in causing such disease is often very difficult to establish for any individual.

Types and Amounts of Benefits

The benefits provided under workers' compensation include periodic cash payments and medical services to the worker during a period of disablement, and death and funeral benefits to the worker's survivors. Lump-sum settlements are permitted under most programs. However, a lump-sum settlement may, in some cases, provide inadequate protection to disabled workers, especially where lump-sum agreements prevent payment of future benefits (particularly for medical care) when the same disabling condition recurs. In many States, special benefits are included (for example, maintenance allowances during rehabilitation and other rehabilitation services for injured workers). To provide an additional incentive for employers to obey child labor laws, extra benefits may be provided for minors injured while illegally employed.

The cash benefits for temporary total disability, permanent total disability, permanent partial disability, and death of a worker are usually calculated as a percentage of weekly earnings at the time of accident or death—most commonly 66⅔%. In some States, the percentage varies with the worker's marital status and the number of dependent children, especially in case of death.

All programs, however, place dollar maximums on the weekly amounts payable to a disabled worker or to survivors with the result that some beneficiaries (generally higher-paid workers) receive less than the amount indicated by these percentages. Five out of six programs have adopted flexible provisions for setting the maximum weekly benefit amounts, basing them on automatic adjustments in relation to the average weekly wage in the jurisdiction. Without these automatic adjustments, annual legislation would be required to increase the maximum weekly benefit amount; consequently, an even greater number of injured workers would fail to receive a benefit equal to the State's percentage.

Other provisions in workers' compensation programs limit the number of weeks for which compensation may be paid or the aggregate amount that may be paid in a given case, and establish waiting-period requirements. These provisions also operate to reduce the specified percentage.

Compensation is payable after a waiting period ranging from 3 to 7 days, with 3 days the most common, except in the Virgin Islands, which pays after the first full day of disability. However, for workers whose disabilities continue from 4 days to 6 weeks, the payment of benefits is retroactive to the date of injury.

Temporary and Permanent Total Disability